For better or worse, I find it impossible to write this

without some initial self-reflection. The line that separates self-reflection

(a sound component of any analysis) and self-referentiality (always rather

embarrassing and at times downright distasteful) is such a thin one anyway. In

this case, the task itself – to sketch my version of Nordic art during the

decade that expired on 31 December 2019 – makes me a little doubtful.

There are two reasons for this.

First, Nordic art is a contested notion for many because

its two constituent parts may be infinitely scrutinised and rejected and

brought back into circulation, but perhaps particularly for me, who was

employed to use these very words and promote whatever they might signify. In

1995–96, I directed the Nordic Arts Centre at Suomenlinna outside Helsinki, and

from 1997–99 the Nordic Institute for Contemporary Art (better known under its

acronym NIFCA) in the same island fortress.

Already then, when global demand for artists and art from

the Nordic countries may have been at its all-time high, Nordic art always

prompted debate (and not seldom dismay). As a notion it was considered

outdated, politicised, bureaucratic – often by the very people who were gaining

most from the increased outside interest. I remember spending far too much time

coming up with sufficiently intelligent “art-specific” ways to retain the

phrase and at the same time allow it to quietly recede.

Second, the 2010s. Apart from the general difficulty of

understanding any decade as it may still be unfolding (remember “the long

nineties” which lasted from summer 1989 until early autumn 2001), the 2010s

were, for myself, not a very Nordic period. For eight years I lived abroad, in

Belgium, and my attempts at following events at home were never very ambitious

or systematic. Nevertheless, I did spend 2010 in Lund and 2019 in Helsinki,

which is at least something.

This task is also complicated by the fact that I, off and

on, have kept more in touch with Lithuania (my second, elected home country)

than with Sweden or the rest of the Nordic region. When I start thinking of

Nordic art in the 2010s, do my memories of Lithuanian (and Latvian and

Estonian) artists I have either worked with or followed belong or not? In any

case, it may be good to remind ourselves that the Baltic nations have very

significantly strengthened their positions in the art world during the last ten

years; this has also influenced their Nordic neighbours.

A new image of the Nordic region, tainted by colonial history

Have we, the Nordics, lost ground to our poorer cousins, who just thirty years ago were the westernmost outpost of the Soviet Union? It is almost impossible to say in today’s ever more decentralised and – luckily, although it is a slow process – decolonised art world. It is unlikely that any country or region of the Global North will ever again experience the waves of interest and investment from the art world’s power brokers that poured in over Britain, the Nordic countries, and Eastern Europe some twenty or thirty years ago.

The exception, perhaps, being the Indigenous Peoples in the far north. When their artists articulate their suppressed, marginalised, and often ridiculed histories and cultures, they represent the decolonisation of the otherwise shamelessly privileged and self-contained welfare states at the outer edge of the European weather map. Try getting a visiting international curator of one of the large Asian biennials interested in any other kind of Nordic art, and you will understand what I mean.

If the covers of the London-based art journal Afterall may be regarded as an indicator (which is perhaps reasonable, although I must mention that I was one of its editors until recently), what they demonstrate is that distinguished female artists rooted in Nordic colonial history now increasingly represent our entire region. The cover of issue no. 44 (autumn/winter 2017) is a photograph of Pia Arke’s (1958–2007) mother, taken in eastern Greenland in the late 1940s, while a detail from Britta Marakatt-Labba’s embroidered history painting Garjját (The Crows, 1981) signals the content of issue no. 45 (spring/summer 2018). No other Nordic artists were featured on the covers of this journal during the 2010s.

If I risk appearing self-referential, it is because decisions I have helped make during the past decade illustrate how the Nordic region and its artists are viewed from the outside by people who don’t have any specific task to promote them or make them visible. I can’t give a detailed account of all the artists and oeuvres I worked with while at Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) – there were hundreds, if the exhibitions and publications showcasing the museum’s collection are included – but I confess to showing less than half a dozen Nordic artists.

Insufficient loyalty towards my own cultural heritage, you may think and say, but this modest figure was already seen by my colleagues and employers as a nearly inadmissible display of patriotism by an otherwise internationally oriented curator. Nordic art is simply not seen as “international enough,” either at home or abroad.

The new demand for a Pia Arke or a Britta Marakatt-Labba also reflects another art world tendency: the ‘rediscovery’ of previously overlooked artists (who should usually be older and preferably female). A very eloquent example of this was the cover of Artforum International in November 2019, dedicated to the Swedish painter Ulla Wiggen (born in 1942 and unnoticed for too long in her own country).

Nordic artists with international traction

This is the new normal after the “Nordic Miracle” of the late nineties, when institutions all over the world suddenly wanted Nordic group exhibitions and artists like Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Miriam Bäckström, Joachim Koester, Ólafur Elíasson or Torbjørn Rødland (and many others) became known to wider audiences. I have often said that, thanks to this abnormal surge in outside interest, Danish, Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish artists no longer had to emigrate to keep an international career going. The situation was and is partly different in Iceland, with its small population and its strategic mid-Atlantic location. Obviously, artists from the Nordic countries were able to make themselves globally known before the 1990s, but then they were usually based in one of the main art metropolises – from Bertel Thorvaldsen in Rome two hundred years ago to Öyvind Fahlström in New York in the 1960s.

Whether this reasoning is still valid today, on the threshold of the 2020s, I don’t know. My informal and very unscientific investigation into which Nordic artists people in the art world (quite a bit younger than myself) recall from the past decade has brought me to the conclusion that the best known are those who for some time have been identified as global players. They therefore spend most of their time outside their home countries and have grown into other social contexts than the art circles in the Nordic capitals. These are still largely characterised by the kind of institutional delays one notices when visiting group exhibitions in larger Nordic museums: Oh, okay, the curator has been to this or that biennial or triennial; well, I already saw this so and so many years ago in this or that major museum.

Writing this kind of column is, as it were, all but impossible without name-dropping. What follows is my enumeration of some artists who have left visible marks during the 2010s and who may be regarded as Nordic – a rather important caveat, since some of them originate from outside the region and are therefore at ease in other contexts than the big Nordic names of the 1990s. Danh Vo will rank high on any such list after his mega-presence at the Venice biennale in 2015 (as both exhibitor in the Danish pavilion and curator at Ponte Dogana), after his solo show at Guggenheim in New York in 2018 and in general as an internationally visible and discussed artist of the first order, although he is still affiliated with Denmark.

Klara Lidén was also frequently mentioned by those I spoke with (who are all artists themselves, I should probably add), and the Venice biennale (the combined Danish and Nordic pavilions in 2009) boosted her visibility as well. Two other Swedish-born artists, both based in Berlin, keep coming up in my conversations: Nina Canell and Karl Holmqvist. As does their fellow Berliner Nina Beier from Denmark, and the Finnish artists Jenna Sutela (who also lives in Berlin) and Pilvi Takala (who used to live there).

I should add Nathalie Djurberg and Runo Lagomarsino, two alumni of the Malmö Art Academy who have successfully exhibited in the international part of the Venice biennale. Djurberg was awarded the Silver Lion in 2009. Lagomarsino partipated in 2015 and was included in a group exhibition at the Danish pavilion in 2011. Among other Nordic artists who have shown outside of the national pavilions in Venice are Ida Ekblad in 2011 (together with Lidén and Holmqvist) and Henrik Olesen and Ragnar Kjartansson in 2013. Meriç Algün, Petra Bauer and Liisa Roberts participated in 2015, and Frida Orupabo in 2019.

Since we are already doing statistics, we might as well take a look at the Nordic ‘results’ of the two Documentas in the 2010s. Documenta 13 (2012) yields nine names: Lea Porsager from Denmark, Mika Taanila from Finland, and the three Norwegian artists Matias Faldbakken, Toril Johannessen, and Sissel Tolaas showed new work. And we mustn’t forget Hannah Ryggen’s grandly showcased tapestries, or the presentations by Erkki Kurenniemi and M.A. Numminen from Finland, and the Norwegian composer Arne Nordheim. At Documenta 14 (2017), on the other hand, no Nordic artists participated other than the Sami: Keviselie/Hans Ragnar Mathisen, Britta Marakatt-Labba, Joar Nango, Synnøve Persen and Máret Ánne Sara.

Two duos also seem to be among the generally well-remembered Nordic artists of he 2010s: Tamar Guimarães and Kasper Akhøj (the international part of the Venice biennale in 2013 and the Belgian pavilion in 2015) and Goldin+Senneby (quite a few biennials, especially in the mid-2010s, but so far neither Venice nor Documenta).

As you will have noticed, the classical – actually Western European – events are still used as criteria for what is worth remembering, or at least for what people really remember after having been there – because they still go there. We mustn’t forget that some Nordic artists, famous since the 1990s, have also exhibited in major – actually Anglo-Saxon – institutions during the 2010s, for instance at Tate Modern, where the most visible ones were Superflex in 2017 and Ólafur Elíasson in 2019. MoMA is a special case in this context, since the only Nordic artists awarded large-scale exhibitions there in the 2010s were Edvard Munch (2012–13) and Björk (the much-derided show in 2015), even if the museum also showed Henrik Olesen (a Danish-born artist who has inspired younger colleagues in the German-speaking world and the Nordic region) and Sergej Jensen, both in 2011, and also (of course, one is tempted to say) Ólafur Elíasson, although only with a smaller project in 2013. Decidedly, however, the most important Nordic artist in New York in the 2010s was, at least in terms of audience numbers, Hilma af Klint. She attracted more than 600,000 visitors to the Guggenheim in 2018–19.

It is not easy to find a common denominator for the artists I have named. Some of them are attentive to the preferences of the market, whereas others regard it with enlightened condescension, or respond to its sudden interest with what seems like incomprehension. Yet as a rule visibility has quite a lot to do with the market, which means that the opposite is also true: even very experienced and relevant artists may find themselves stuck in the shadows cast by the attention economy.

There are artists who remain forever topical, but at the same time curiously marginalised, as if someone wanted to illustrate the expression “best-kept secret” at their expense – at least in relation to the outside world. Lars Englund (Sweden, 1933) and Magnús Pálsson (Iceland, 1929) must still, unfortunately, be counted among those, even if the latter was given a substantial retrospective at the Reykjavik Art Museum in the autumn of 2019. No doubt there remains an unknown number of other artists across the region who should be given more attention and be contextualised in new ways. Perhaps the time will come also for Pamela Brandt (Finland, 1950), Jessie Kleemann (Greenland/Denmark, 1959), Eva Larsson (Sweden, 1953), Sinikka Tuominen (Finland, 1947), and Thorvaldur Thorsteinsson (Iceland, 1960–2013).

There is no Nordic art scene, and that might be a good thing

Perhaps such lists are meaningful, perhaps not. One advantage of mentioning names is that they signify concrete empirical knowledge. Behind a name is a person and their work, not a synthesised theory of current reality or a series of detached observations which may be misleading. It is a pity that it can be so hard to remember a name when you need it most.

Throughout the past decade, the artists I have managed to name here, as well as many others, have worked to secure the quality and credibility that would have constituted the foundation for a Nordic “scene” – had such a thing existed. I don’t think it does now, since the motivation and the infrastructure are both lacking. Perhaps this is a pity; perhaps it doesn’t matter that much. The notion of the scene is often overrated, and creating a scene through artificial means may lead to mediocrity. Indeed, the purpose of my text is neither to revive a lost sense of togetherness, nor to create an overview of Nordic art during a decade that may represent ‘business as usual’. Instead, I want to convey how hard it can be to zoom in on the concrete meaning of a notion that was always fluid, always questionable.

One source of information about the Nordic art scene that I have chosen to use rather sparingly is the Nordic pavilion at Giardini in Venice during the five biennales between 2011 and 2019. These exhibitions (put together according to different principles, since the pavilion was consecutively programmed by each of the three “collaborating” countries until 2017) are made by specialists from the region, and therefore don’t always capture the dynamic between its self-image and how it appears to others.

What was really going on in Nordic art during the 2010s, under the tyranny of “smart” telephones? Or rather, what are artists in and from the Nordic countries doing today, when the world has simultaneously become more streamlined and much more fragmented than before? Aren’t we all reading the same anxiety-inducing news items about koala bears incinerated in Australian bush fires? Does anyone, on the other hand, know what anyone else is doing, thinking, or feeling when we are all linked-in with the same all-seeing eye?

Scattered new generations

Young artists (the term is hard to define exactly, but these are generally people born in the 1980s and 90s) from the five countries and three self-governing areas which still make up the Nordic region in the official sense probably don’t feel much closer to each other than they would to anyone else unless they happen to be personally acquainted. And that is only a real possibility if they have studied together at one of the art academies in the region – because there are almost no other institutional meeting places left after the demise of NIFCA some fifteen years ago.

In previous paragraphs, I have been able to assume that readers know the oeuvre behind the artist’s name, since so many of my examples were selected from contemporary art’s international and institutional mainstream. Without venturing into a proper status report, and even less into some kind of prophecy for the decade ahead, I want to mention some younger artists from the Nordic countries and very sketchily describe ‘what they are doing’. As in the art world in general, it seems reasonable to make a distinction between two kinds of artists: those who in their work address certain topics – the popular ones today are, just like in the 1970s, the environment, gender roles and computerisation – or move in a certain direction formally or technically; and those who have either come to see every topic as a limitation or just haven’t confined themselves to a certain message or aesthetic.

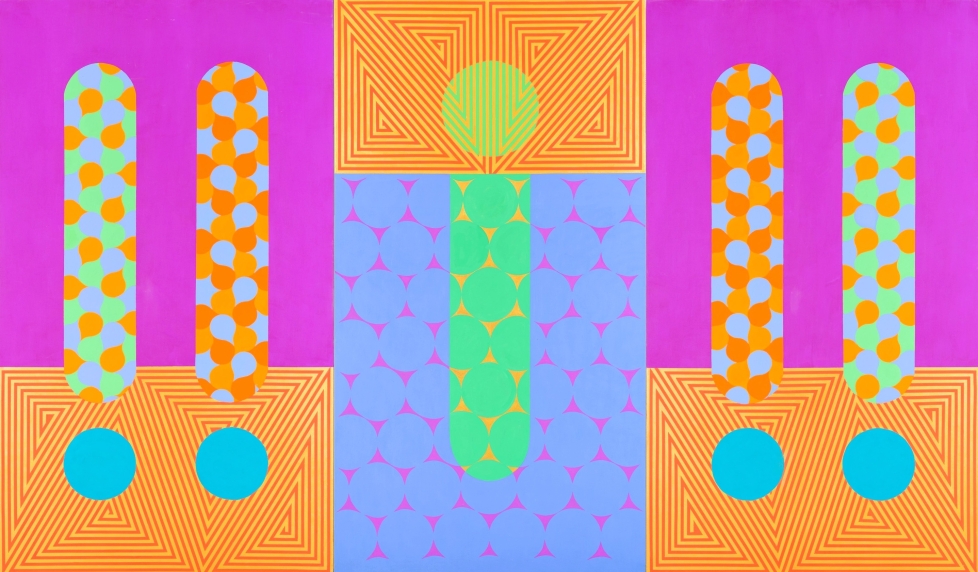

Among the former, I would consider straightforward painters, for instance Erla Haraldsdóttir (Iceland, 1988), Alma Heikkilä (Finland, 1984) and Fredrik Værslev (Norway, 1979), and those who are more or less unambiguously sculptors, such as Jóhan Martin Christiansen (Faeroe Islands/Denmark, 1987), Tiril Hasselknippe (Norway, 1981), Juha Pekka Matias Laakkonen (Finland, 1982) and Anna Uddenberg (Sweden, 1982). Despite the fact that these artists differ so much from each other, formally and in terms of ideas, what they show us is the diversity and fluidity of the art field, rather than some kind of lingering genre-specific predictability.

Of course, all those who use their practice as a tool to advance a particular agenda or actively covet the role of “influencer” should also be considered part of the first group. Some examples: Arvida Byström (Sweden, 1991, with her 230,000 followers on Instagram); Maja Malou Lyse (Denmark, 1993, with her sex education programmes for Danish TV); also those acting outside of the whiteness norm, such as Nayab Ikram (Åland Islands, 1992), Makonde Linde (Sweden, 1981, whose performance Painful Cake went viral in 2012) and Sandra Mujinga (Norway, 1989).

Among those who evade all attempts at categorising, I would like to consider Jaakko Pallasvuo (Finland, 1987, who is perhaps best known for his auto-fictitious comic strips on Instagram, but is also a writer, draughtsman, painter, and video artist) and Eugène Sundelius von Rosen (Sweden, 1991, also active in the comic strip scene and at the same time a published poet and a performance artist).

One topic so pressing and ubiquitous that it can no longer be considered a special interest is the climate crisis. Another is what is now known as surveillance capitalism, which provides the logic behind artificial intelligence as an everyday threat, as well as other side effects of life online which are becoming ever harder to fathom. No matter how eclectic, introverted, medium-specific or socially engaged these young artists are, they can’t escape these fundamental conditions of contemporary life.

The hybridity that nearly all younger artists channel today should probably be regarded as an inevitable consequence of contemporary disorientation and precariousness. The problems and the means for expressing despondency over them are global. The only thing specifically Nordic about these particular artists might be the local accent that can be sensed behind their fluent English (more often than not with an American twang): Södermalm, Alppila, Drøbak, Frederiksberg, or another similar microcosm. Whether they and their colleagues from older generations put any premium on belonging to a certain nation or region is a question that should perhaps no longer be asked. In this respect, the Nordic region has become more international than ever.

We who work in the art world and are not artists must continue to help reshape and recreate Nordic art and its place on the international arena, whether we actively use the notion or not. In this compressed text, I have chosen only to name artists and let the importance of curators and other organisers remain implied. That mustn’t be seen as sign of disrespect for my colleagues. I just wanted to use my limited space to plead for the “old-fashioned” point of view that the limelight of the art scene ought to shine firstly on those who use their own selves – decade after decade – as material for showing us other members of society who we might be or become.

Anders Kreuger (Sweden, 1965) has been active as a curator, writer and educator for two decades. Since last year, he is Director of Kohta, a private kunsthalle in Helsinki. He moved there after eight years as Senior Curator at M HKA, the Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp. In the 1990s he directed NIFCa and the Nordic Arts Centre at Suomenlinna outside Helsinki. Kreuger contributes to Kunstkritikk with some regularity. In 2012–18 he as a member of the Editorial Team for the London-based art journal Afterall.