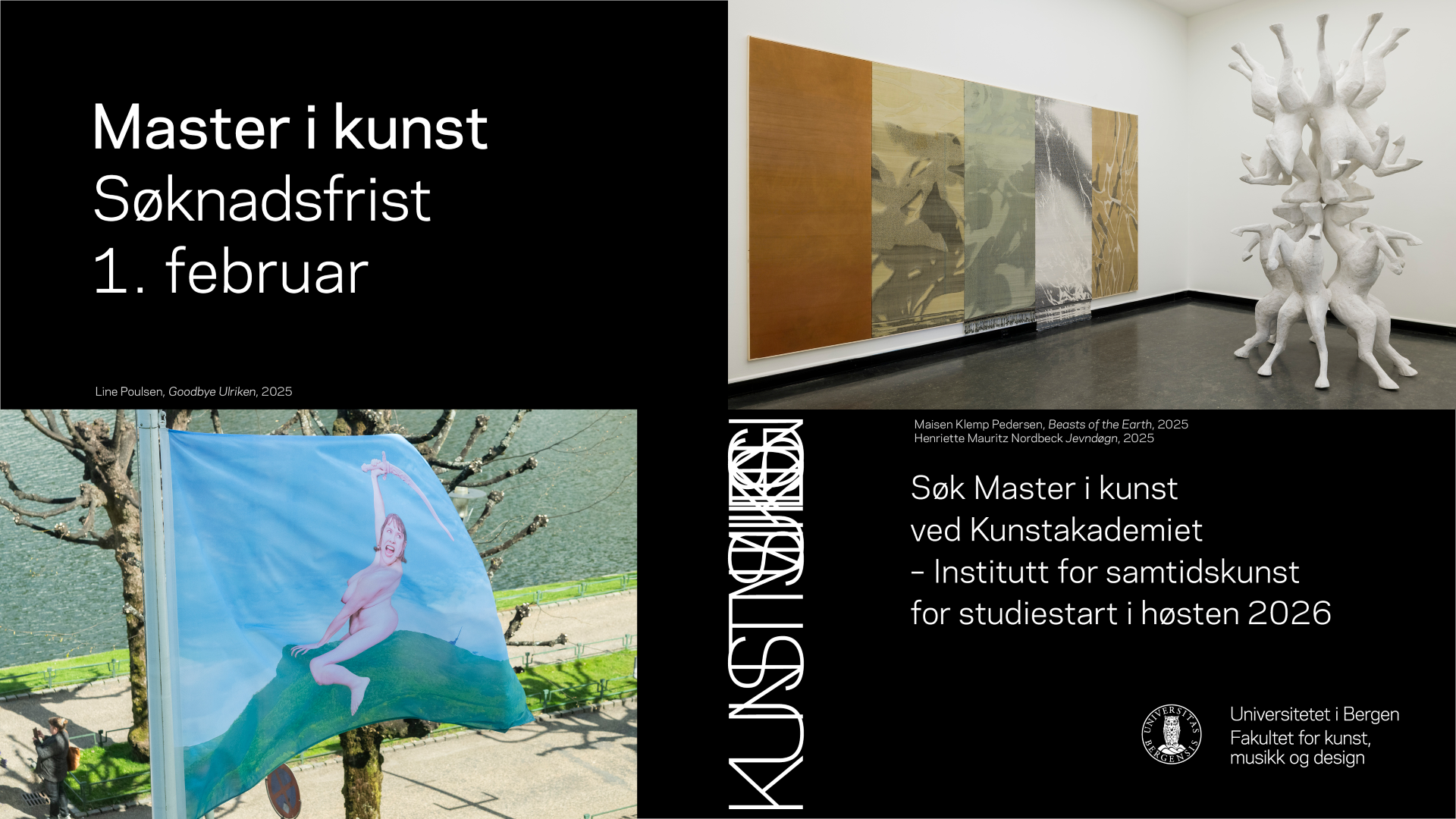

“Can we have another one? And this time a bit friendlier.” At the gallery in Munich, the photographer is trying to get a smile out of Kirsten Ortwed, but she’s not having it. Ortwed is in futuristic-looking Prada sneakers and a leather jacket. Some large stone sculptures are scattered on the floor. Her exhibition at Galerie Jahn & Jahn opens tonight.

“Sculpture is body that meets body in a space,” wrote the painter Troels Wörsel in a text for Ortwed’s show at Horsens Art Museum in 2000. He describes how she uses “negative shapes as a way to make space visible,” and how her works argue, as in math: QED. In other words, their presence alone ought to be enough. So what does the artist need to stand there and smile for?

Ortwed met Wörsel in an explosive collision in 1979, when he lived in Munich. Later, they would move to Cologne together. But I don’t get this story until later. Ortwed had her first show with Fred Jahn in 1982. Jahn und Jahn are father and son, Fred and Matthias. Ortwed has known Matthias since he was “this small – ten centimetres between index finger and thumb.” The Jahns belong to the old guard of galleries that over the course of the last fifty years have shaped the art market as we know it today. The same goes for Galerie Nordenhake in Stockholm, which also used to have a space in Cologne, and on whose roster Ortwed has also been a staple for a lifetime. It’s a scene.

Galerie Jahn und Jahn is in the backyard of a stylish postmodern complex, and continues to evoke the eternal allure emitted from the Rhineland during the 1980s – the good old days when the art scene was scaled to size, and the level of glamour somewhat within reach. Ortwed too possesses this vanishing je ne sais quoi. We met around a bonfire on Bornholm island this summer, when she instantly commanded the whole party’s attention with her stories of the old farmhouse she bought and is in the process of renovating. It was obvious that there was more for us to talk about. Back in Munich, the photographer packs up; Ortwed and I go outside for a cigarette.

Out on a limb

The exhibition at Jahn und Jahn is called Head Turned. It’s a reference to an experience, a movement: while driving down the road, something catches your eye, and you turn your head. It might be that you have to keep driving, but you already know that, at some point, you’ll have to go back.

“That’s always how things start for me. That initial impulse, and the fact that you choose to respond to it. In this case, I happened to pass a stone yard that never usually has anything interesting, and I saw this huge block. It’s Mexican onyx, you almost can’t get it anymore,” Ortwed relays energetically.

Possible Result of a Crafty Noise and Turning Time are two groups of sculptures, one from a block of stone from Turkey, the other from Mexico. They look like leaves or paper – something light and crumpled, tossed aside, but large (each one is almost a metre across) and solid.

“A third of the stone I can’t use at all, but you have to buy the whole thing. You’ll spend 100,000 kroner in an instant, so you’re out on a limb. But, of course, you just have to do it. The challenge is to chop into the stone in a way that brings something interesting out in it. If you start off the wrong way, it might look like shit. You never know, but you can learn to sense it. At the same time, I wanted it maximum 5 cm thick. It’s risky risky risky because it can so easily break. It’s a hell of a time, but when you want something, you have to do it. And in that critical phase, there is a very special vibe that just absorbs you completely.”

It’s a very special vibe that the works transmit into the space. It springs from the contrast between the real weight of the stones and the elegant way in which they only just touch the floor, as well as their almost impossibly wild patterns: stripes in shades of red, yellow, black, and white. It’s quite clear that they are beautiful, but I have also understood enough about Ortwed’s work to know better than to point that out.

Hers is a pretty uninhibited and formalist kind of art, in the end – a far cry from today’s more cautious discursive tendencies. Ortwed’s work depends on a considerable amount of courage, just as it employs materials and is of a scale that the artist necessarily feels entitled to write herself into certain histories and assume certain spaces. I am trying to understand where this comes from. How do you become an uncompromising Rhineland sculptress? Is there a recipe you can follow?

“When I was young, I had never been to an exhibition. I was afraid to even go in there! But then I’ve always been making stuff,” she says. Making stuff? It is as if, for Ortwed, the concept of art is self-evident. The creative act is the whole premise.

A Riot

Because Ortwed was always ‘making stuff’, she was keen to study at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen. Her parents didn’t think it was a good idea. “That pissed me off, and so I left home to travel around Europe” – alone and with 600 kroner to her name. It was the early 1960s, she was 16 years old. Nothing was planned, and she stayed in each place for as long as it was interesting. At some point, she boarded a train to Venice. “What a rowdy place it was back then, gloomy streets, a real port town where you’d eat a bowl of spaghetti in some dingy backroom.” She then continued onwards by ship to Turkey. Perhaps her parents would have preferred her sitting around at the art academy. But “that wasn’t how it was,” she says, somewhat opaquely. “I was myself, you see, pretty radical.”

Upon her return to Denmark a year later, Ortwed lived alone in her grandfather’s house in Holte, a suburb of Copenhagen, after he moved to a nursing home. “We had a riot out there, one party after another.” Those were anarchic times, she explains: “We didn’t want to be subservient to the system, or the authorities. And people were experimenting with all sorts of drugs. Man, those were some crazy trips. There are two years of my life I can’t even remember. It was messy, but here I am, still. Old, but strong. Holte was quite the hangout. A lot of them died from overdoses. I’ve never been a junkie; I’ve never shot up. And the ones that died, they shot. But then at a certain point I thought, hell, party’s over, time for a change. And then I applied to the academy.”

Throughout her youth, Ortwed did a bunch of different jobs to get by. While she was studying at The Royal Academy, she worked as a cleaner at a hospital. “I would show up in the morning straight from a party, but there I was anyway with the broom in my hand, totally wasted. Things were like that back then. No one was rich, and no one I knew talked about money. I remember my friend, the painter William Skotte Olsen, lived in an apartment somewhere with his mom who was in a wheelchair. The whole place smelled like pork roast and potatoes. His room was very, very small. But that’s where he stood, by the wall directly across from the bed, and made his huge paintings. Today everyone talks about money. I am very thankful to have experienced a time when what was important was what you did and the ideas that you had.”

Always onwards

The environment that Ortwed enrolled into at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 1972 could not have been more different from her transgressive and anti-authoritarian Holte-gang. “I remember opening the door to the classroom and seeing them all sat there in front of a model, drawing. I just closed the door again and thought ‘you’ve gotta be kidding me’. Then I heard the principle say that ‘we are not counting on the women, anyway’. So that was the lay of the land: You had to be just as good as the men and better, and, besides, not fuck around with anyone at all. Otherwise – as it happened to some of the women there – you’d be labelled a ‘prize-fucker’.”

Back then, the teaching staff consisted of artists such as Svend Wiig Hansen and Richard Mortensen who were mostly associated with post-war abstraction. In that context, Arthur ‘Addie’ Køpcke was groundbreaking. Køpcke had moved from Hamburg to Copenhagen in the late 1950s, and had connections to more radical tendencies south of the Danish border: Fluxus, performance, Beuys.

“He was a crucial figure who showed a way beyond what was already established. When Addie left, I went to Gunnar Aagaard Andersen, which was alright. But after two years it was a bit like the parties in Holte. You start to lose yourself in the fogs. I took my diploma in 1975. It was time to move on.”

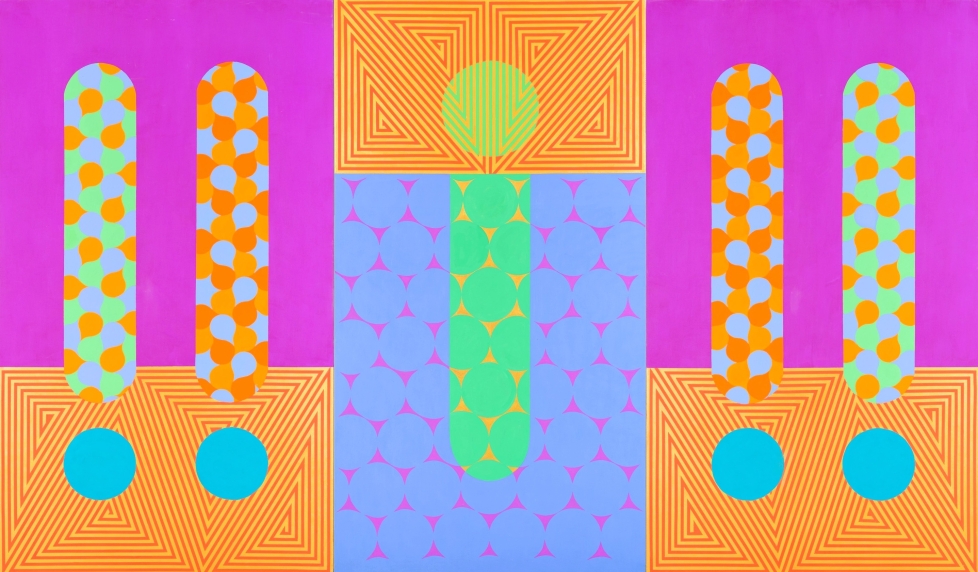

Moving on is, in many ways, Ortwed’s modus operandi. First she went to New York in 1976, and then to Cologne in 1982, where she has since lived. Artistically, it was a matter of departing from the slightly dull conceptual and minimal art prominent at the time. But it was also always a practical and material exploration of what it is possible to do – what happens if you subvert techniques, or take a different road from the obvious one.

We bop around in Jahn und Jahn drinking coffee while the staff see to the last details. Tim Geissler, partner in the gallery, is on his knees wiping the floor beneath one of the sculptures. Later, there is a small dinner in typically Bavarian style: Schweinehaxe and Wurstsalat. But everything has become so boring. I barely even made it to Munich from Berlin because of the coronavirus restrictions, and now here I am, more or less alone in the great beer halls. “The restaurants stop serving alcohol at 22.00, so we have to order a lot just before, so we get to stay a bit longer,” Ortwed advises. “Otherwise, what’s the damn point?” We both agree.

It is clear that the social aspects of being an artist have always been central to Ortwed. “All of the people I’ve known, I’ve really had a blast,” she says, recalling her year in New York. She was in her late twenties and became friends with the team behind Saturday Night Live. “I’ve never laughed so much in my entire life.” When Ortwed does something, it’s because it’s important. But that doesn’t mean that it shouldn’t also be fun. In a way, her work is characterised by the same odd pairing of the stringently formal and other more figurative, almost silly, elements.

Cultivating coincidence

In the Munich exhibition, the onyx sculptures are accompanied by a lineup of smaller works that all retreat towards the wall. In Waiting is a yellow foam corner on a platform that hides a mess of green strings underneath. Spinning Off is a pile of clay sausage shapes wrapped in a colourful piece of fabric. A rustic block of stone has the word ‘Modello’ attached to it in unevenly sized bronze lettering. There’s a cheekiness to the smaller works that unsettles the gravity of the stone sculptures.

“It’s cool to break the seriousness. It’s a kind of joke I have with myself. Here I just put some polyurethane foam into a corner between some boards. It’s not like I plan it out. I just take things that I have standing around left over from other projects. It’s almost like drawing; there’s a refreshing informality to them that shows another side of me.”

The incongruence helps keep the viewer alert. There is not, as in minimalism, a dogmatic aspiration to material or methodological purity. You never know exactly what to expect from the work, or how stable its ontology actually is. What’s uncompromising in Ortwed is less about the work’s relationship to itself than the brazen assurance with which it meets the world. As she puts it: “I have always tried to avoid having a style. Especially when I was young it was the worst thing imaginable. Everything always had to be in a new way.”

In this way Ortwed has cultivated a kind of aesthetics of coincidence independent of social, political, and academic discourses – for instance about gender – or even the cultural connotations of a concept like beauty.

“I happen to think that the Random Walk-series is extremely beautiful,” the German artist Rosemarie Trockel noted in an interview with Ortwed for the catalogue accompanying the latter’s exhibition at the Living Art Museum in Reykjavik in 1992. The two artists are close friends, and Trockel was being purposefully provocative. With Random Walk, Ortwed let lumps of clay fall from a forklift at different heights, and then cast them in bronze in whichever way they had landed. Bronze, not because it is beautiful or noble, but because it makes the most accurate reading of the material. It is a way of granting a special significance to the arbitrary.

In the interview, Trockel asks:

What does beauty mean to you?

Ortwed replies:

– Beauty doesn’t mean anything to me.

And criticism?

– Not important.

And what about gender – is that important to you?

– No. You see, I decided very early on, already when I was still at the academy, that I wouldn’t let it impact how I work as an artist. And that’s also how I’ve lived.

Ortwed and Trockel’s conversation is interesting because it stages a cool and objective artist-persona that not only allows Ortwed to occupy a hard position, but, perhaps even more so, encourages reflection on the question of positioning as such. What does it mean to declare yourself independent? It might be precisely in the circumvention of style that we find Ortwed’s signature, after all.

The horror of kitsch

When Ortwed exhibited in the Danish Pavilion in Venice in 1997, the Italian port town had grown less dodgy than what she had experienced in the 1960s. Without ever having visited a Venice biennial before, she moved into the prestigious space in the Giardini with an exhibition concept that bordered on invisible.

“I wanted to use the negative forms of big sculptures I had made the year before for public squares in Års, a town in northern Jutland. I cast them in aluminium, and then had them sandblasted. When you sandblast aluminium, it’s as if you’re killing it; you deaden its surface; it becomes a non-material. It could also have been concrete, but it had to be transported.”

The dead surface, the negative form. In the Venice installation, the absence of style speaks its own clear visual language. The aluminium sculptures flickered on the floor – not unlike the onyx pieces in Munich – together with piles of metal chains. Both the moulds and the moorings are essentially secondary objects, types of infrastructure. But in the context of Ortwed’s installation, they assumed a new kind of substance as a presence that also contained what wasn’t there.

It was around the same time that Ortwed won a competition to make a public memorial for Raoul Wallenberg in Stockholm. During the Second World War, Wallenberg, a Swedish diplomat, was stationed in Budapest, where he saved 100,000–200,000 people from being deported to the extermination camps by issuing impromptu Swedish passports.

Ortwed’s winning bid was inaugurated in 2001, and consists of twelve figures in bronze. The figures are oblong and box-like, but irregular, interrupted, and arranged in a dynamic constellation towards the harbour. It makes quite an unsentimental impression, one without much tearful self-affirming heroisation. This became a challenge for the work’s reception. “It wasn’t supposed to be a Holocaust memorial, but was often taken that way,” Ortwed tells me. “Even before it was installed, it was fiercely criticised.”

Memorials are frequently expected to make amends for something by offering a straightforward representation that calls for a particular emotional response in the viewer. But Ortwed’s work doesn’t tell us what to think or feel. Six male artists had been invited to partake in the competition, and Ortwed describes several of their entries as “more overtly Holocaust-related” – in some way figurative, or symbolically explicit. The art historian Rosalind Krauss has referred to architect Daniel Libeskind’s proposal for the Sachsenhausen concentration camp memorial as “the horror of kitsch.” Perhaps Ortwed would agree. “I didn’t want to represent Wallenberg himself, but describe his actions. A lot of people had a problem with that.”

In that case, Wallenberg’s actions are described by the herd of sculptures as the disruption of a powerful motion. Like mountains that rise when one tectonic plate presses itself upon another, Ortwed’s box shapes break out of their own forms. Wallenberg’s signature is laid into the floor of the square, contributing the communicative element that always helps to balance Ortwed’s compositions. It is possible that she doesn’t have a style, but here I am starting to recognise her language. So many young artists have this restlessness about them. They are looking for something, and perhaps assume that what they are seeking is a topic, or an argument. But when I look at Ortwed’s hardcore bronze-fleet, it’s obvious that what these young artists are missing is a language.

“People want to be able to explain everything in life – also art – and that is precisely what art doesn’t allow you to do,” said Ortwed in 2000 in a conversation about the Wallenberg commission. “It’s not possible to relay the atrocities and terrors of the past. Rather, I wanted to create a group of sculptures that contains dignity – that has freshness, speed, and a certain confidence.”

Love and Liberty

The day after the opening, Ortwed and I are having lunch at Schumann’s, another one of the mythical postmodern troughs that the German art world revolves around. There’s an old-fashioned self-evidence to this place: the fittings are crafted from solid walnut, the martini tastes like a diamond, and an exceedingly thinly sliced roast beef has been on the menu since before the wall came down.

Of course, it’s fully booked – Munich’s entire art scene is power-lunching with ladies in Escada twinsets – but Ortwed is old pals with Charles, and so a table is found. He brings us a special serving of his famous Bratkartoffeln “in memoriam.” I love listening to other people’s love stories, and have made a note to myself: “Ask about Troels.”

Troels Wörsel was a Danish painter, and he and Ortwed lived and worked alongside one another for the better part of the last forty years until he died in 2018. They moved to Cologne together in 1982, and since the 1990s have lived partly in the artists’ haven Pietrasanta in Tuscany.

“I met him for the first time in 1979 because I had a fling with one of his friends who was a writer. Troels had gone to Munich four years before, but we were familiar with each other’s work. We met in Copenhagen with this writer, and just fell in love. I mean, crazy in love. The writer was going to London the next day, so the coast was clear. We hung out the whole day and the next night, and just talked and talked. It was as if lightning had struck. It was the whole package. It really was.”

That was exactly what I wanted to hear. The whole package. Sigh.

“But we never worked together artistically, and that was wise. I would have sworn, ‘never an artist; anything but an artist’. We had our own studios, our own separate finances. You know, I can spend a ton of money on materials. He was an expressionistic painter. Damn, he was good. And a good thinker and skilled writer. We didn’t always see eye to eye, but we shared the same perspective on art: that it shouldn’t be necessary to read a lot and understand a lot, but just be able to see when something is good. It’s extremely important that something comes across in the moment you see a work or art. We didn’t speak in the way that you do today. We could just tell when there was a connection. When you work with art yourself, you have a special understanding for other art, too – that is, if you’re able to see beyond the end of your nose, and we both were,” Ortwed says, puts her fork down and straightens her back. These are some heavy memorial Bratkartoffeln. So many years. Troels.

What I understand by ‘speak in the way that you do today’ is: academic, theoretical. Even if we are talking about an embodied experience, it sounds like that: ‘embodied experience’. Today, the equivalent of Ortwed’s confrontation with the establishment has become a type of discourse, a smothering and didactic concept of art. Young people are either married and knocked up in Hay-furnished apartments, or afraid of love. I scan the room, looking for Charles. Need more Riesling.

“I never wanted to get married. I never wanted to end up as someone else’s possession. I couldn’t bear the thought of losing my freedom, how degrading that would be. Back then, being a woman artist was a pretty hopeless job. You had to deal with all kinds of crap. That has changed. Today you can still be an artist even if you’re married with children and all sorts of things. But it’s clear that from my generation of woman artists in Germany, no one has kids. Not Rosemarie, not Astrid Klein. It would have been impossible to do what I have done if I also had a child. I’m not the type for it.”

Later on, when I recall that afternoon in the gallery, and Ortwed’s absent smile, it strikes me that it’s similar to a scene in Sylvia Plath’s novel The Bell Jar (1963). Her protagonist, an intern at a women’s magazine, is having her picture taken. “Give us a smile,” they keep saying, but she mostly feels like jumping out of the window. When Plath published her novel, Ortwed was a teenager on her way to Turkey by boat from Venice. Or high as a kite at the hangout in Holte. “I was myself, you see, pretty radical.” An absent smile is a liberation from expectations, a rejection of a certain idea of womanhood.

Today, her strategy also works as a bulwark against the pressure to perform one’s identity, and the eternally personal and sentimental that structured the reception of the Wallenberg work.

Now Ortwed is making a hangout on Bornholm. She’s renovating a dilapidated farm outside the tiny village of Østerlars. “Getting old is not so bad. It’s actually pretty cool. It’s not like anything is over. It’s only over when everything is over. I’m very busy; there’s so much to do.” For one, the island needs a contemporary art centre. “On Bornholm, you can’t even say that the schnapps are few and far in between. There are no schnapps.” We call Charles.