“The speed of light. That is the big question. Can we reach or even exceed the speed of light?” This question is asked by a spokesman of Deutsche Bank, one of the main characters in Hito Steyerl’s film Factory of the Sun – and a telling mixture of shrilly coke-addled TV-infotainer and prototypical Nazi Baddy.

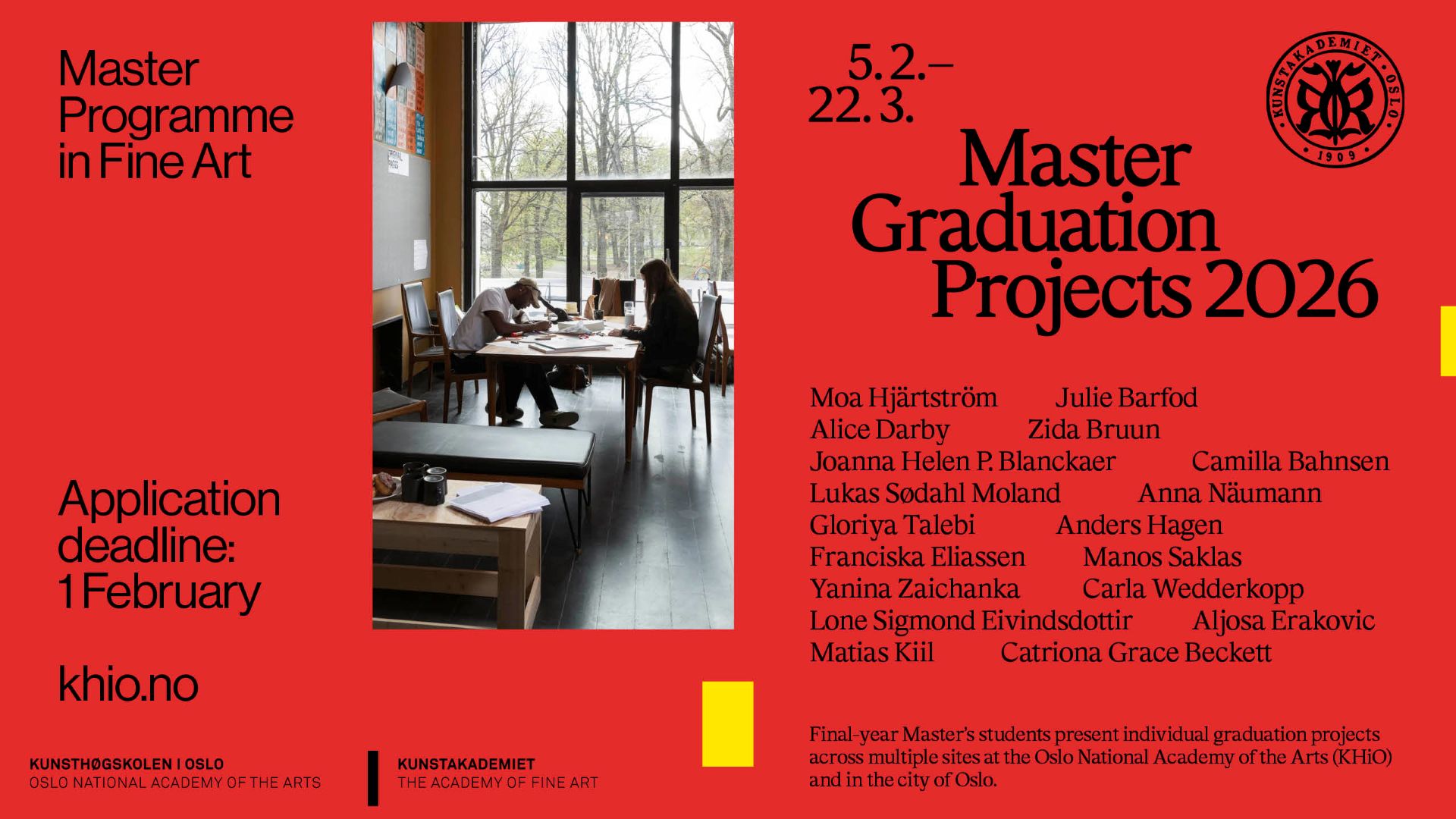

We are at Kunsthal Charlottenborg in Copenhagen, which is currently home to Steyerl’s celebrated and much-debated Factory of the Sun, a work originally created for the German Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennial. For professional art audiences this is likely to be a repeat view, and the work not only bears up a second viewing. It deserves it, too.

The reason is simple: Underneath the spectacular surface glitz that gave Factory of the Sun its blockbuster status, an essentially obvious, yet seemingly overlooked point lies hidden: that digital capitalism borrows its Utopian vision from pre-modern alchemical metaphysics that has nothing to do with the secular society advocated by the Enlightenment era. Much more on this later.

The film is installed within a black box where luminous blue lines form a grid across the floors, ceiling and walls – an obvious nod to the cyber film classic Tron (1982), in which Jeff Bridges’ gamer-geek character is sucked into the computer of a software company, engaging in a struggle for liberation against the hegemony of the operating system that enslaves the company’s employees, forcing them to fight out deadly gladiator battles in a virtual ‘game-grid’.

By using this device, Steyerl deftly places his audience in a poignantly paradoxical situation right from the outset: the virtual space has become reality around us. The internal has been made external, and even as passive spectators we are always already deeply embroiled in the power games of capital. Why the sun chairs? Because we bask and sun ourselves in the light from the screen, and because the “factory of the sun” is more than anything a metaphor for the technological sun’s triumph over the real sun in an accelerated capitalist endgame that aims at making light, capital and information merge to become an absolute form of power.

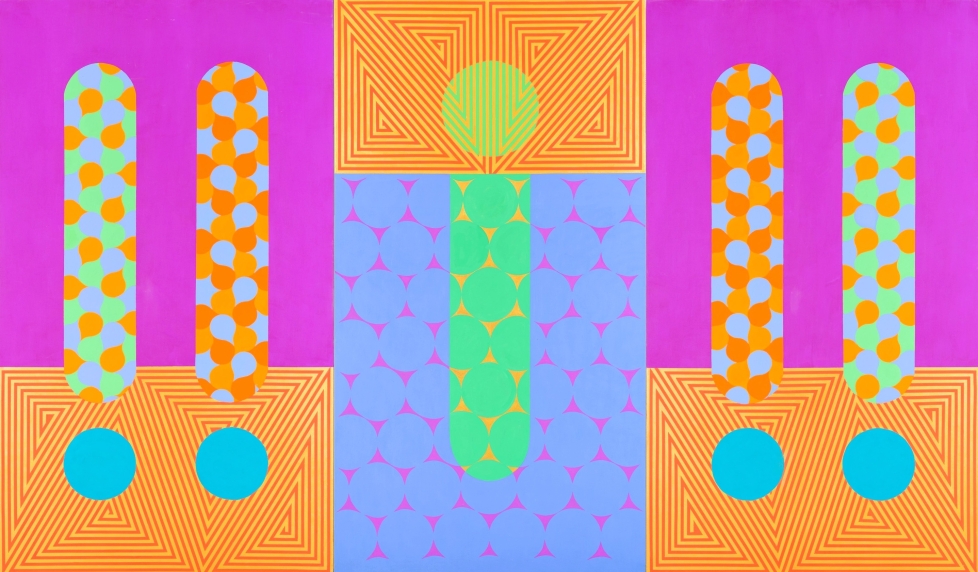

Factory of the Sun is best described as a meta-documentary about the ultimate fantasy of capitalism. Stylistically this is a dopamine-heavy mixture of a computer game, music video, infomercial and documentary. We are introduced to the game programmer Julia, who explains our task as players in this game grid: “This is your mission: You start off as a forced labourer in a motion capture studio. Every movement you make will be captured and converted into sunshine.”

In the film, the forced labourers of the digital economy are represented by super-funky dancers in gold jumpsuits. Their creative moves are captured and translated into luminous capital. All body movements are tracked with a view to control and monetisation. One dance scene takes place at the former NSA listening station Teufelsberg in Berlin, while another is set in a teenager’s bedroom in Canada, telling the story of a dancer whose movements became the starting point for a series of animated figures that take on life of their own online.

With funky ease Steyerl takes the spectator through a dense, labyrinthine web of real and virtual locations, meta-mediality, paradoxical games of meaning and a concrete narrative. While this may sound messy and complicated, it is in fact done with surprisingly effortless elegance in the film itself.

One of the key features of the work is the life story of game programmer Julia, who describes a historic transition away from a Cold War reality dominated by Wall and Iron Curtain to a digital reality dominated by Screen and Cloud. Steyerl seems to be making the point that this historic shift – related at breakneck speed through Julia – has not only changed the balance of power in a geopolitical space; the digital revolution has also brought about a kind of metaphysical mutation that has fundamentally changed the rules of society and its plays for power.

This point is reflected in the film’s overall link between dance, light and capital. For just as dance strives towards abolishing gravity, hypnotising us with movements that seem physically impossible, capitalism too strives towards an absolute mobility and movement, ultimately wishing to transcend the laws of physics. In the film the spokesman from Deutsche Bank assures us that the bank will certainly accelerate the speed of light, even if the experimental physicists at Cern are faltering in their experiments.

This endeavour to go beyond the laws of physics is based on magical and metaphysical thinking. In this regard it seems obvious to view the ‘sun factory’ as a technological update of a classic alchemist’s laboratory with its glassware, distillation apparatus and burners. This is also why we see golden electric bulbs gush forth from a computer screen, and the reason why the dancers are dressed in gold suits.

The popular notion about alchemists – that they were simply seeking to produce gold in order to make money – is a huge and infantilising misunderstanding. The alchemists’ true dream is described in the Magnum Opus, which means ‘the Great Work’. Many different editions exist, dating from the early medieval era to the late Renaissance. The book describes an all-encompassing magical and metaphysical vision that ultimately aims to create Lapis Philosophorum – the Philosopher’s Stone. This was imagined to be magical matter, a liquid luminous gold that could be used to transform any material into any other material. Also, Lapis Philosophorum was believed to grant access to absolute knowledge and bring eternal life.

This is to say that Steyerl creates a link between alchemical thinking and capitalism in the digital paradigm, and this is where the work truly begins to peak in terms of conceptual content. Why? Because our so-called modern secular democracies are simply based on the division of light, its splitting in two. Here light comes in two forms: the light of knowledge (enlightenment) and the light of religion (faith). One of the fundamental terms of modern democracy is that these two aspects of light must be kept separate. The light that Thomas Edison captured in his light bulb is the light of reason and science by which the modern institutions were to be enlightened, whereas the sacred light of religion should only illuminate the soul.

Factory of the Sun showcases a deeply confusing paradox: our so-called secular democracy is controlled, mediated, recorded and played back by light machines that are not based on such a division of light, but rather on a thoroughly transcendental metaphysics of light that precedes modernity and is rooted in alchemy. “Our machines are made of pure sunlight,” as the dancers say in the film.

Within the alchemical interior of the sun factory the secular splitting of the light is reversed, fusing all light once again in one and the same fibre-optic cable. We hear a sentence repeated over and over: “All that was work has melted into sunshine” – a paraphrase of a famous passage in the Communist Manifesto stating that “all that is solid melts into air”. In the age of digital capitalism all matter is translated into information – that is, light.

When one of the dancers in Factory of the Sun bends light, saying “I can reverse light into itself,” he is actually saying this: I can make fiction become reality and reality become fiction – I can transform science into conspiracy theory and conspiracy theory into political truths, for it is all just a question of reversing information. Fundamental political views are replaced by conspiracy theories, and enlightened arguments are replaced by info-wars and fake news.

This logic of transmutation, where anything can be reversed into anything else, is an alchemical concept that has risen again in the age of digital capitalism as a paranoid patriarchal power fantasy. The word “matter” shares the same root as the word “mater” (mother), and most myths describe the Earth as female while the sun is male. Thus, “All that was work has melted into sunshine” means that everything that springs from the Earth (which is, in a mythical perspective, female) is transformed to a single, patriarchal-panoptical form of power that rules from the cloud.

Factory of the Sun shows us that power is now simply the manipulation of information and light. If you think this sounds somewhat speculative, you can simply consider the recent cases involving hacking in the recent American presidential election, or Donald Trump’s use of the data analysis company Cambridge Analytica in his campaign.

From a mythical-religious perspective, manipulating light is tantamount to manipulating the sacred, which can be more or less regarded as the definition of magic. Factory of the Sun forces its viewers to realise this: The emergence of the digital paradigm means that all social theories must be entirely rewritten because their analyses of power have never been interested in magical thinking, whereas information technology is obsessed with it. As classical metaphysical horizons prompting a transcendental desire, the Sun and the Sky are dead. But with the advent of the Screen and the Cloud they have risen again as interior techno-metaphysical horizons that once again animate a transcendental desire for absolute knowledge and eternal life – for total power.

With Factory of the Sun Hito Steyerl offers up a perfect diagnosis of our times with all that this entails of slick meta-mediality and zany cosmological thinking. But towards the end she prescribes medicine with no real impact. The film ends on a note akin to a socialist manifesto for the digital age: “All photons are created equal! No photon should be accelerated at the expense of others! Resist total capture!” It is hard to imagine that this Utopian notion of equality could ever truly escape the black box in which the work is installed.

If reality in the age of digital capitalism is a game animated by a myth underpinning it all, what would it take to change the reality of that game? The logical answer would be: another myth! For only another myth can transform the transcendental desire that drives evolution towards transforming all material reality into “machines made of pure sunlight”. The first precondition for establishing another myth is to recognise that we already live in one. This point should be amply illuminated for all after a trip to the factory of the sun.