This must be the first time I’ve imagined what an exhibition would look like at night, alone, in the moonlight. In Chechen-born artist Aslan Goisum’s show at Lund Konsthall, this effect is mostly provoked by two works reminiscent of cemeteries.

In the front hall, the iron fences of Object (2022) have been put up as if on a graveyard without graves. The installation’s pared-down expression underlines that the cemetery is a place everyone can relate to. Its sibling on the upper floor, Table (2024), is a tabletop with a miniature city consisting of roof-like structures that might belong to chapels or mausoleums. Here we observe the cemetery from the outside, a view reminding us that we, the passers-by, are mere visitors, that these graves don’t belong to us.

In Fearsome (2011–ongoing) and Numbers (2015) Goisum has gathered old street signs from Grozny, the city of his birth. Arranged in grids, the distressed enamelled plaques evoke both political history and visual memories of growing up during the catastrophic wars between Russia and Chechnya (1994–96, 1999–2009). I also understand them as early examples of the artist’s attempts at translating personal experience into abstract form.

My moonlight fantasy had nothing to do with some eerie feeling in the exhibition, but with how the works activated a body memory that I apparently associate with night-time. Form giving rise to bodily perception is, I believe, the exhibition’s main theme, since practically all the works are about the feeling of what something looks like. The sculpture Star (2024) looks like a deconstructed star-shape, where the feeling of the points has been enhanced.

Similarly, Spear (2023–24), a series of wall-hung sculptures comprising books wrapped in pink paper and subjected to painstaking cuts – almost like little cakes – embody a visual-tactile longing; they materialise the feeling of slicing through the books as if they were butter.

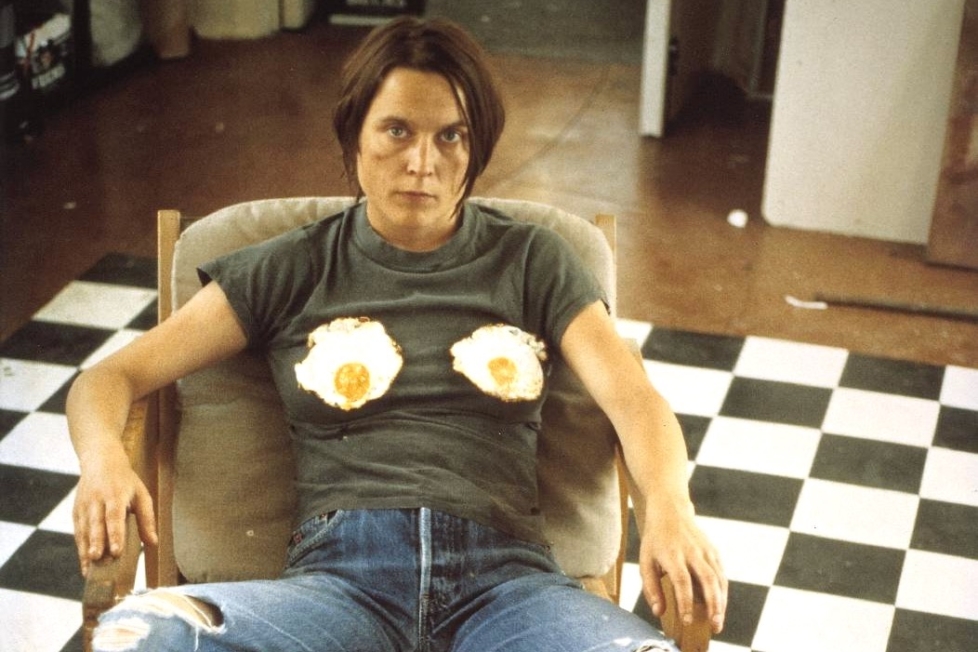

The most striking work here is Prism (2024), which also lent the exhibition its title, a seven-metres tall video sculpture in the rear hall. On three LED screens forming a straight column, a film sequence shows a naked young man moving his hands over his own body. It is an excellent use of the space, where the work can be seen from the balcony on the upper floor and where the form divides the work into three parts that can never be viewed simultaneously. This is a profoundly sensual and hypnotic work with echoes of advertising billboards and statues of Christ. It may appear to be the complete opposite of the abstract sculptures but works in the same way, using simple means to activate a body memory in the viewer.

Goisum’s exhibition is sparse, and those uninterested might hurry through it in five minutes. But the simplicity contains precision: the forms communicate. It is as if they are only pronouncing single words – death, house, then, you, he, she – but that is enough to set something in motion. These are wonderful examples of art that marries hard-edge abstraction with the flesh. Whether you are interested or not, the naked body in Prism will stop you in your tracks.