As I make my way to meet Jeremy Deller on an afternoon in November I have this inner image of a giant, grizzled man in a permanent state of inner turmoil. Nothing could be further from the truth – the real Deller is nothing like that – but somehow the artist’s mural from the British pavilion at Venice last summer, showing William Morris in the act of crushing a giant yacht, has embedded itself so firmly in my mind that Deller the person has become identical to his work. An absurd fallacy, and my error is only aggravated by the fact that over the course of his 20-year career Deller has only very rarely used autobiographical material in his work. Rather, collective works – processions, historical re-enactments, and social stagings – have become the key hallmarks of Deller’s art. Kunstkritikk met him to talk about his very first exhibition, on how his contribution to the British Pavillon on this year’s Venice was all about revenge, Hans Haacke’s stubborness towards the art market as well as his most recent challenge: creating a proposal for the memorials that will honour the victims of the attacks in Norway on 22 July 2011. What Deller’s proposal will be is revealed tomorrow when he and the seven other participants, Jonas Dahlberg, Estudio SIC, Goksøyr & Martens and Snøhetta Architects, Olav Christopher Jenssen and LPO Architects, Haugen/Zohar Architects, Paul Murdoch Architect and NLÉ & Kunlé Adeyemi show their models and sketches at Rådhusgalleriet.

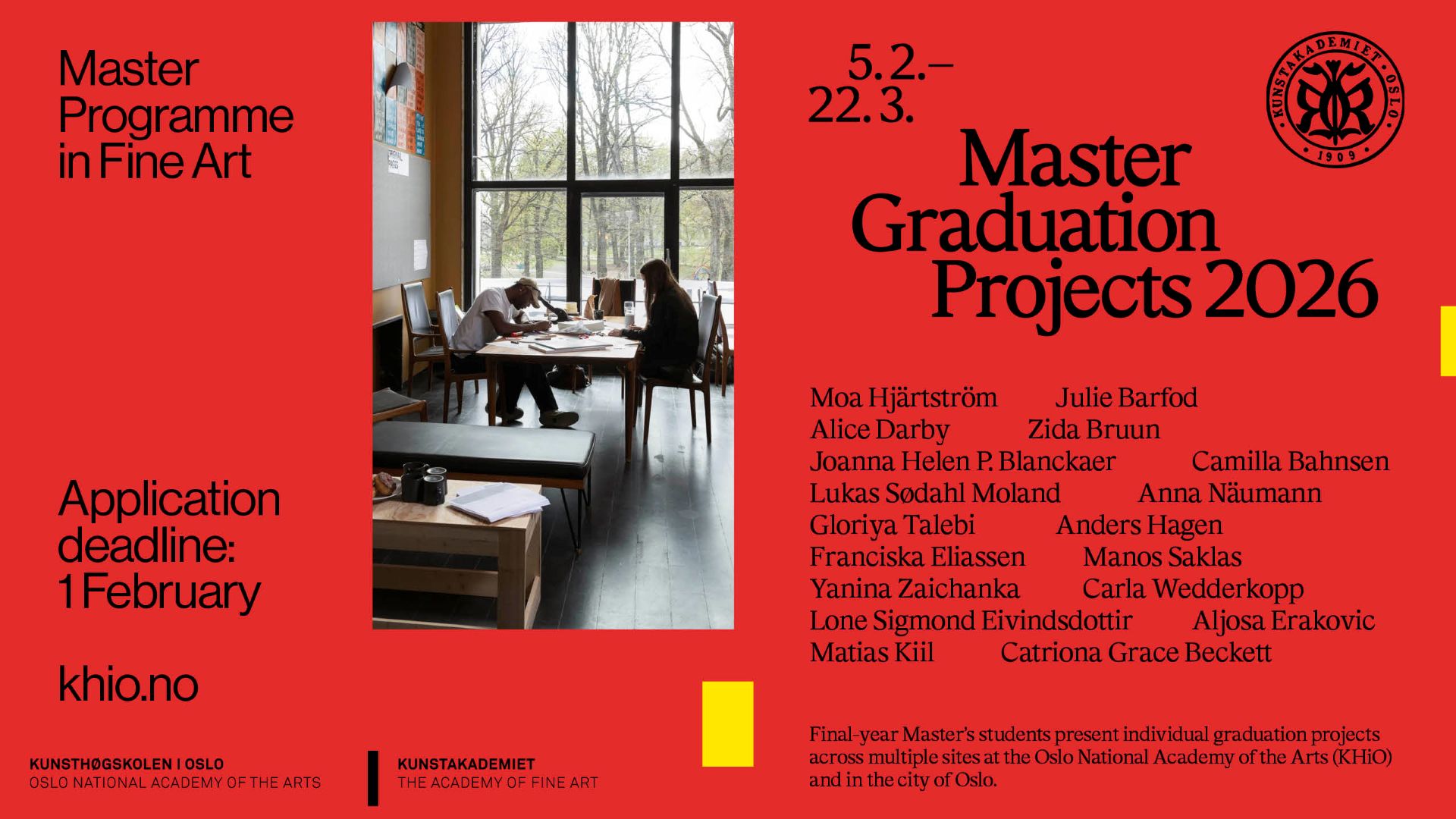

Your first exhibitions, Open Bedroom, took place when you were thirty. Still living at home, you seized the opportunity to use your house as a site for a show when your parents went away on holiday. Reading about it, I couldn’t help getting curious about your background.

I come from a very normal middle-class background in South London. I was taken to museums and galleries quite a bit as a child. After the age of twelve I was banished from art class, and later on I never trained as an artist. Instead I studied art history, not contemporary art but Baroque art, mainly Spanish and Italian. So I know a lot about those things, or not a lot, but a bit a bit turns out to be a masters degree, the journalist notes).

Class issues are a recurring theme in your art. In what ways has your background affected you as an artist?

Well, I don’t think my background has much to do with it. You just pick that up living in Britain. I went to private school, and they kept telling us that we were better that other people because we belonged to this class or this school. So you are always aware of it. But it was a very different kind of milieu from the one I was brought up in, which wasn’t so elevated and class conscious.

Meeting Andy Warhol as a young student was crucial for your decision to become an artist. I have read that when Warhol unexpectedly placed his hand on your knee, you felt that as a massive compliment?

It wasn’t my knee. It wasn’t that innocent. I introduced myself to him when he visited London in 1986 and me and a friend was invited to his hotel suite were he was chilling out with his entourage. He invited me to The Factory, and when I came to New York and saw how it worked I just thought, ‘this is an amazing life to have, filled with freedom’. I was only twenty, so I wasn’t really sure what I was going to do, but the experience made art history look very boring. I went back to college, and kept on studying. But I was ruined by then. It had ruined me, but that was fine.

There is a strong political nerve in a lot of your work, most explicitly maybe in The Battle of Orgreave (2001) – a re-enactment which brought together around 1,000 persons to restage the clash between miners and police in Orgreave, Yorkshire, that took place during the war between Thatcher and the National Union of Mineworkers in 1984. How did you become interested in that part of Britain’s past?

I wasn’t interested in it, I lived trough it. I was seventeen and though I didn’t take part in it myself I was part of that climate, that background. The strike went on for one year and was on the news all the time, so it was something that I always wanted to look at again. The re-enactment consisted of 1,000 people. About 200 were former miners, and then there were relatives and local people and members of historical re-enactment societies – people who normally dress up as roman centurions or Napoleonic soldiers – that came and re-enacted this battle.

When I look at the video documenting the re-enactment the first thing that strikes me is that there is a lot of rage?

The real battle looked very different, much more dangerous and many more people. But there is still anger there.

Did you think of the re-enactment as a therapeutic work?

Not really, if anything it’s the opposite. I didn’t want people to think afterwards that it was all okay. If anything I wanted people to become angrier rather than less angry. People tend to interpret art as a way of healing, but some times art is there to provoke. So it was meant to be provocative, not cathartic.

How is the situation in these former mining communities today?

It is quite bad, they are still quite poor. There is not much employment, not much money, a lot of drug problems. These towns were built on an industry, and when the industry leaves they have to find new purpose. On the whole there is a big disparity in the UK between the north and the south, and between London and the rest of the country. That difference has gotten more extreme since the battle in 1984. So the problem is still there, and that’s why Margaret Thatcher, who decided to close down the mines, is not forgiven.

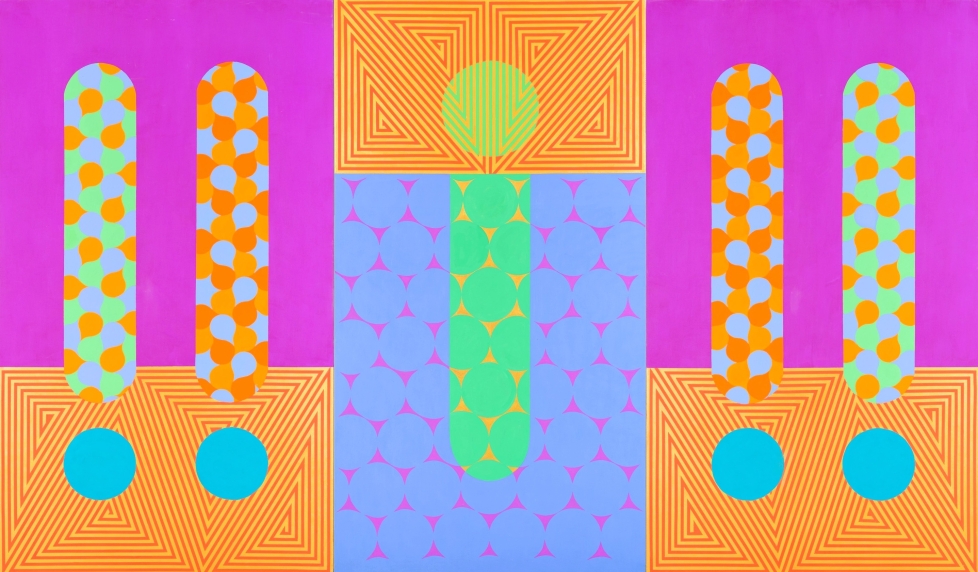

Last year you filled the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennial with the project English Magic. One of the works was a mural depicting William Morris coming back as a giant, standing in the Venetian lagoon destroying Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich’s monstrous yacht that was moored outside the Giardini during the 2011 biennial. You have summed up the project as being about revenge and destruction.

It is, in a good way. It’s poetic revenge, poetic justice. It is things being destroyed that I would like to seen destroyed by giants and giant animals, so it’s a mythological side to my work in Venice that resembles pre-Christian and folk mythology.

And you believe bringing that dimension to political art is a good idea?

I think it’s good. It gives political art a poetic element rather than being against this or hating that. And it gives it humour as well, which could be important. Politics on the whole is very lacking in humour and fantasy.

William Morris initiated the Arts & Crafts movement, and a lot of people only know the aestheticised part of his project; the beautiful fabrics, woodcuts etc.

Exactly, those are things that represent great beauty. He was an extreme character, he had quite extreme beliefs about politics, production, and art’s place in society. That’s what’s so interesting about him, he made these objects of great beauty, but he was also a very political person. He wanted to bring back dignity and worth to labour and to craft. Often politics and beauty don’t go together at all. Politics is ugly, its iconography is usually not very good and the art for politics is often not so great either.

Today we see Morris’ designs as very middle class. But he was a great follower of Karl Marx, who was living in London at the same time. I don’t think they met, but Morris was one of the first people to set up a socialist party in London. He gave lectures about socialism, about the working man’s role in society and the dignity of work, and about the factory system being iniquitous. So he was very aware of the human cost of the industrial revolution and he hated it, because he saw people being exploited.

At the same time there is a fear of modernity in Morris’ project, isn’t there?

Yes, though he wrote a science fiction book describing an ideal future, he was actually quite backward looking. He didn’t like the ways things were going. You have to remember that British cities in the 1880s were pretty horrible places; he saw people being sick, children working and all that. He was also critical towards British exploitation abroad; the empire and slavery. At the same time he was a very successful businessman, within that there are contradictions. Even Marx was quite a contradictive character. He liked bourgeois life, but also he wanted to destroy it. These men are quite contradictory, but that’s what makes them interesting. They are not boring people.

Charles Dickens’ descriptions of the poverty and the hard work that the working class had to put up with in the 19th century could be easily be used to describe the lives of city dwellers in the third world today, many of them producing most of the goods we are consuming. Do you think that Morris’s utopian socialism has any relevance for today?

I have no idea. Maybe as a role model for artists as someone that really believed in something and was willing to put his beliefs out there and suffer ridicule. That is quite unusual now. People are so sensitive, I am as well.

Using Morris as a destroyer of luxury and decadence in Venice might also point back to the art world?

Absolutely. Another thing about Abramovich is the source of his money. That room in the British Pavilion didn’t just have a mural; it also contained documents that attempted to explain how he and other oligarchs became rich very quickly without creating or inventing anything. So you could see that room as an epic tale where Morris is the beginning of an idea – socialist idealism – in the UK at least, and Abramovich and other oligarchs is the end of Communism. So it’s like the beginning and the end of something.

But it’s not only Russian oligarchs that are showing off their splendour in Venice during the biennial. The mixture of fashion, glamour and spectacle infuses even the art world, and Venice seems to be a pinnacle of that?

It could be, but I think the pinnacle really at the moment is Art Basel at Miami. I just looked at photographs of it. It looked unbelievable. People go there to launch perfumes or cars. It is used as a backdrop.

Art has been full of critique of capitalism for the last 10 or 15 years, but this criticism rarely examines the dependence on capital within the art world, the way Hans Haacke did in the 70s or 80s?

It is difficult because you end up making your living by creating art about the art world being terrible which you then sell to people in the art world. Haacke has very high standards, which I think are impossible to keep. Either you are in the art world or you’re not. Haacke is definitely in the art word, but he pretends he’s not.

So there is a lack of self-awareness there?

I think he is a bit naïve. I shouldn’t really say that because he is obviously a great artist. I once saw him give a talk were he said he would never sell his works at art fairs. But if you have a gallery there is not much difference between doing a gallery show and an art fair. It is the same market; it’s the same ting.

You seem passionate about ordinary people’s lives. In Folk Archive, you have made a collection of objects witch touches on subjects such as Morris dancing, gurning competitions, and political demonstrations.

I wouldn’t use the term ‘ordinary people’. I don’t like that therm. Maybe you could say people that aren’t in the art world. I have always been interested in folk art; artistic production that isn’t in the art world, and that is what that exhibition and book is about. If you like art, you should like most art, not only art made by professional artists. If a child makes something I’m interested, and if Caravaggio makes something I’m interested. I’m quite happy to look at both.

Your way of dealing with history is both playful and political. One fantastic example is the bouncy castle modelled after Stonehenge that you made last year and that toured Britain as part of the Olympic Games. What was the idea behind that project?

I had a stupid idea that I thought would be quite good. As the Olympics were coming up and everyone was going on about British identity, I thought I would make a series of inflatable buildings under the heading “secret or forbidden spaces”. The others were secret government spaces, there are a few in Britain, such as listening centres which are public in the sense that you can drive past these closed structures in remote parts of Britain. But in the end it was only Stonehenge that was realised.

Stonehenge is also a place with a lot of different cultural identities connected to it?

Yes, no one knows the original use of it and never will, so it’s all about people projecting their own identity and beliefs onto it. Which is exactly what national identity is; it’s a personal thing. Stonehenge is very much like British national identity; it is indefinable, a mystery, and I think that’s a good ting.

Some of your unrealised projects have been «recycled» in a project called My Failures containing ideas that didn’t quite come off, like the bombed-out car from Iraq that you proposed as a sculpture for the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square. Several conceptual artists have cultivated the noble art of unrealised work or proposals – so I have to ask; is an unrealised idea necessary a failure?

Not really, I just though it was a good word to use in an exhibition and a book. And since artists really don’t talk about those things I thought it was quite funny to call them failures. When people see a retrospective exhibition or a big book about you they expect it to be a celebration about how amazing you are, so it is good to have a section about failures in it.

You are here in Oslo because you have been invited take part in the competition on three places commemorating the victims of the terrors on 22 July 2011. What are you thoughts on this project?

It is too early to say what I’m going to do. I was very surprised when I was asked to partake in this project. You can call it an honour in some ways, and at the same time it’s a very interesting challenge. At the moment I’m just trying to think about what’s possible and what would be most appropriate.

How can one commemorate an event like that?

If you can commemorate the Holocaust you can commemorate anything. And still, stating the obvious, no tragedies are alike. In Britain we lived through terror in the 70s and 80s with the IRA, and I remember hearing a bomb that went off in London when I was young. No single event in the UK was quite as bad as what happened here in Norway on 22 July. But there were three terrible bomb attacks in the high street, assassinations, and more than twenty years of paranoia.

Norway had no prior experience with terror before 22 July. It is a very peaceful, low crime-rate country so when something like that happens it has an enormous impact on society because what surrounds it is peace. In additions there was the shock that the terrorist was someone from within the country, a threat that could not be diminished as an external threat. In a lot of terrorist attacks there is no face to be associated it with, they are almost anonymous, and if people are caught it is often years later. But here perpetrator was a recognisable human being, a seemingly resourceful young man.

Finally, how should a commemorative site like this function?

There is a need for a place where the public can visit and pay respects, and feel that they are part of something. And it should be a place for contemplation. But in the end it’s not for me or anyone else to say. You can’t impose or dictate how a monument like this should be used. The public must decide, and then through a kind of agreement and adoption.