Inför sin retrospektiv på Kiasma diskuterar Eija-Liisa Ahtila hur hennes verk förvandlas i relation till olika utställnings- och distributionsformer. Denna intervjun är översatt från finska till engelska.

Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s exhibition Parallel Worlds takes over Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma in Helsinki this Friday. The current themes of Ahtila’s work are humanity, animals and nature. Her studies on the moving image and philosophical films on biopolitics, post-humanism and war, are represented in this exhibition by both new and old works.

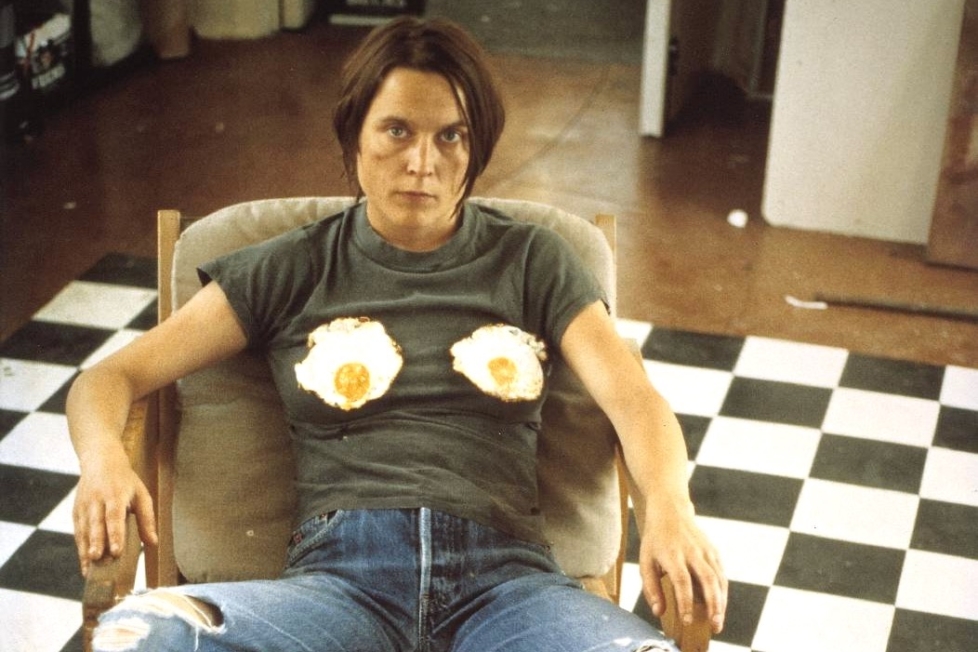

Known for her unique mode of expression, which has been widely appreciated in the film world as well, Ahtila has won prices with classically cut, one-screen films, but the main format of her work is for the installation, in which screens surround the viewer.

The exhibition is organised by Kiasma and Moderna Museet in Stockholm and has been on view in Stockholm and at the Carré d’Art in Nimes, France.

You have divided your work between at least two different institutional platforms, the film world and the world of contemporary art. How did this take place, initially?

In the 1980s I worked with Maria Ruotsala and we attended a video course together. At that point we had been going a lot to the movies. I had graduated from the art school in Helsinki – to be a painter – but I wanted to study film. Well, I painted for one year, and did some installations, conceptual art, etc., but film felt like an interesting medium, and it just took over. I studied in London for a year, and after coming back I first made a work in the manner that would become my way of working. Then I continued my studies in UCLA in Los Angeles. I usually do a gallery version and a museum version of the film, and later on another one for film festivals. The more I worked with the moving image, the more possibilities I saw in it. Maybe because of my perspective, coming from the arts, I saw it as a medium to study and experiment with. «What can you do with it?», I asked myself. And I found myself between two worlds, with a foot in each.

How have the interpretations of your movies been in these two worlds, with their differing traditions of seeing and interpreting moving images?

They are very different. In 2011 I was invited to be a jury member at the Venice Film Festival – the main jury – and they wanted to show my film The Annunciation (2011) as the ending film of the Orizzonte series. I was shocked while I saw my film there. After all that action-based drama I felt that it did not work out very well at all. When it was shown at the festival in Oberhausen the audience was very different and had a totally different attitude towards movies – it won a prize. Everything felt so different. Contexts are important, and these two are just film contexts. For my part I think that the films I make are at their best in museums and on multiple screens. There is not just one system. This experience has been very important for me.

What about short film? Do short film makers know what happens in the art world?

Short films are usually made because people want to make feature films, but it is good to hear from an outsider that film works out fine in the gallery and museum context. There are many people in the contemporary arts who work mainly with film, like Isaac Julien or Shirin Neshat. In a small country like Finland it is absurd that people can ignore films just because they are shown in the «wrong» institution.

Did you have any key technical challenges when you started working with film?

Well, this use of multiple screens… When I studied film in the US I saw these huge advertisements that had still images on them, and some of them had been divided into many parts. I thought that could be something interesting to try with moving images too. Then I saw Gary Hill’s exhibition where he had been thinking about the same thing. He had several different shots and they ran simultaneously. If 6 was 9 (1995) was then realized in Stockholm for a solo exhibition, and there I really used the technique for telling a story for the first time. I had to learn everything in and by making it. Later I became interested in what happens when the filmic event is situated in different places and then in an installation positioned to surround the viewer. But I have still always also done a version for ordinary film distribution. With my last work, The Annunciation, I even ended up producing two different versions for classic film presentation. One unfolds with one picture image, and the other has three images next to each other. This has to do with the theme. In this work, the one picture version seems to work out better than the others, but there is no rule for it. It depends on the work in question.

In the Nordic countries I think you are often seen as a «media artist», but I would rather think of your work as political.

You can mean many different things with politics. The moving image is a medium that in our society is most used to describe and reveal something about our society and world, and so it is very political by nature. What should be shown and in what way? People see a lot of American movies, and you can see it in the ways they reflect visual reality. Everything different makes a political difference. But of course some ideas conveyed can be very political for me as well. Where is where? (2009) is about a true story which happened during the Algerian Civil War. Two thirteen-year-old Algerian boys killed a French boy, their friend. I found the story in Franz Fanon’s book The Wretched of the Earth (1961). It is a one-and-a-half page sequence. Fanon, who was working as a psychiatrist in the hospital where these kids were taken, had to interview them. For me this was not just about French and Algerian history; it was European history as well, and our own. As a coincidence it was shown first in Paris in 2008, in the Jeu de Paume museum. Outside of the exhibition space we had nationalists demonstrating against it. Even in the art circle, people were actively opposed to it. How could a Scandinavian woman understand this, how can she even imagine that she does? But this is actually the question of the work. It is about gaps separating cultures and religions. Could it touch us? How could we discuss this act of violence? And in what way? These are important questions.

Diskussion